“Learning from Nature”

I attended a recent MLA roundtable on Sustainability and Pedagogy that had me thinking (again) about the relationship between the environmental/ecocritical content some of us teach and the ways in which we teach that content. As eco-conscious teachers, it’s often difficult to help students find a place between the paralysis caused by feelings of helplessness about environmental degradation and the glorification of “Nature” as something pure and, therefore, worthy of preservation. My larger research project is interested in texts that exist in those in-betweens, particularly in the first half of the twentieth century.

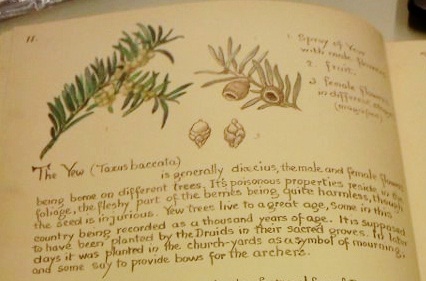

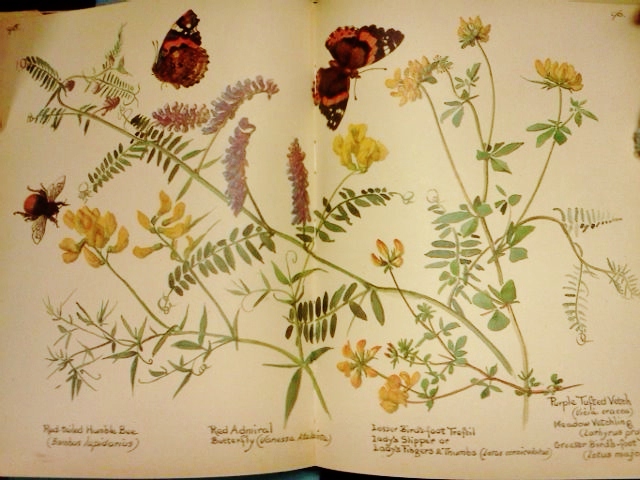

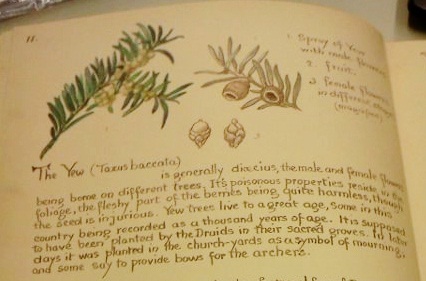

This post is about a mixed-genre text, created by Edith Holden to chronicle, month by month, the activity she observed in the landscapes around Olton, Warwickshire. The collection, titled Nature Notes, 1906, weaves together folklore, poetry, journal entries, watercolors, botanic information, field notes, and more.

The book was never meant for publication, but in 1977 it was printed in facsimile under the new title The Country Diary of an Edwardian Lady. The change in title forebode its reception in the late twentieth century: it became a best seller, inspired a popular biography (by Ina Taylor, 1980), and spawned a 12-part TV miniseries. Reviews and spin-offs of Nature Notes have tended to focus on the text’s “nostalgic charm,” yet Holden’s text was intended, not as an ornamental coffee table book, but as a practical model for her students at Solihull School for Girls where she taught art from 1906-1909.

To a great extent, the teaching that occurs in this text is implicit, subtle, even circuitous. It is teaching by example or model, not by explicit instructions. “This is how you might go about it,” the text seems to offer.

The practice of learning from nature has a long history that continues into the twenty-first century (see biomimetics). Gardens, especially, have been used to teach children and young women how to become well-behaved members of society since at least the eighteenth century. Holden’s field books continue this tradition by expanding the didactic space of the garden to the “wild” spaces of uncultivated landscapes. As a result, these “wild” spaces no longer seem dangerous, threatening, or uncontrollable, but instead become associated with domestic(ating) practices like drawing and flower arrangement. It seems no accident that the pages of Holden’s text are populated with images of flowers, birds, and butterflies with only the occasional reptile, amphibian, or stinging insect.

What a lovely post! A great example of how to blog about research in an engaging and accessible way – enough to make me want to browse through earlier posts. I still haven’t worked up the chutzpah to do this on my own blog, which says a lot about the reader-anxiety that often comes with doing a PhD (where you assume that any reader will be critical, and can’t imagine one who might just be interested). This post just goes to show that, with the help of a creative ‘midwife’, good research speaks for itself. I’m looking forward to your popular academic book 😉

Thank you for your kind comments!

Agreed — a very lovely post. Much of my scholarly work involves archival research, and I often struggle in terms of not only how to blog about my work, but also how I might incorporate some of the more interesting archival documents I discover. I like how you’ve linked this historical document to (more or less) contemporary texts.

Speaking of, do you see any connection between the “rediscovery” of Holden’s work and the prevailing forms of environmentalism in the 1970s? Did the reinterpretation of Holden’s work in the book and the miniseries speak to nature enthusiasts, especially women, who felt “left out” of the emerging environmental movements?

Great questions! Her books (and associated paraphernalia) certainly speak to nature enthusiasts, especially women, and they are also a different kind of response to “nature” than the kind of discourses that emerged during the environmental movement of the 1970s. For the most part, I’ve been contextualizing her works in the historical moment in which they were produced (1905-6), but your comment has made me think about how the publication and reception histories are also deeply tied to a particular historical zeitgeist. Sarah Edwards has published more about the women readers of the books. If you’re interested, the article can be found here: https://pure.strath.ac.uk/portal/files/249818/strathprints005489.pdf

This is a fascinating post that has certainly made me think. There are of course several ways in which ecology is invoked in relation to my area of interest writing and education. But this takes these ideas in an entirely different direction.

Quite recently I reviewed a book about literacy and education in which the writer refers to the ‘garden becoming a text’. The statement has remained in my mind as something that intrigues. There is perhaps something about how the garden becomes a space to share ideas, to generate and agree plans, to inscribe memories and create new ones – to leave a trace and a record.

Az

http://azumahcarol.blogspot.co.uk/2013/01/national-researchcentre-improving-adult.html